Wai Horotiu Queen Street Project

UPDATE Nov 2022

It’s a pleasure when it appears feedback is actually heard

The new layout actually works

What a surprise to find the final version of the Queen St refit actually works well for cyclists. The final two blocks near the ferry end of Queen St still require the same treatment, but unless budget cuts bite, that should finish it off well.

One does still need to ask why during Covid $840,000 was spent, even if 90% was central government funding, on the yellow plastic sticks and the raised bus landings that angered shopkeepers, looked horrible and wasted taxpayers money

The Original Plan Did not

Below is the feedback SlowCycles provided to AT. In summary it stated that mixing buses and bicycles was a very bad idea, especially with such a narrow lane. It seems AT and Auckland Council took this feedback on board.

Wai Horotiu Queen Street Project

What’s wrong with this picture?

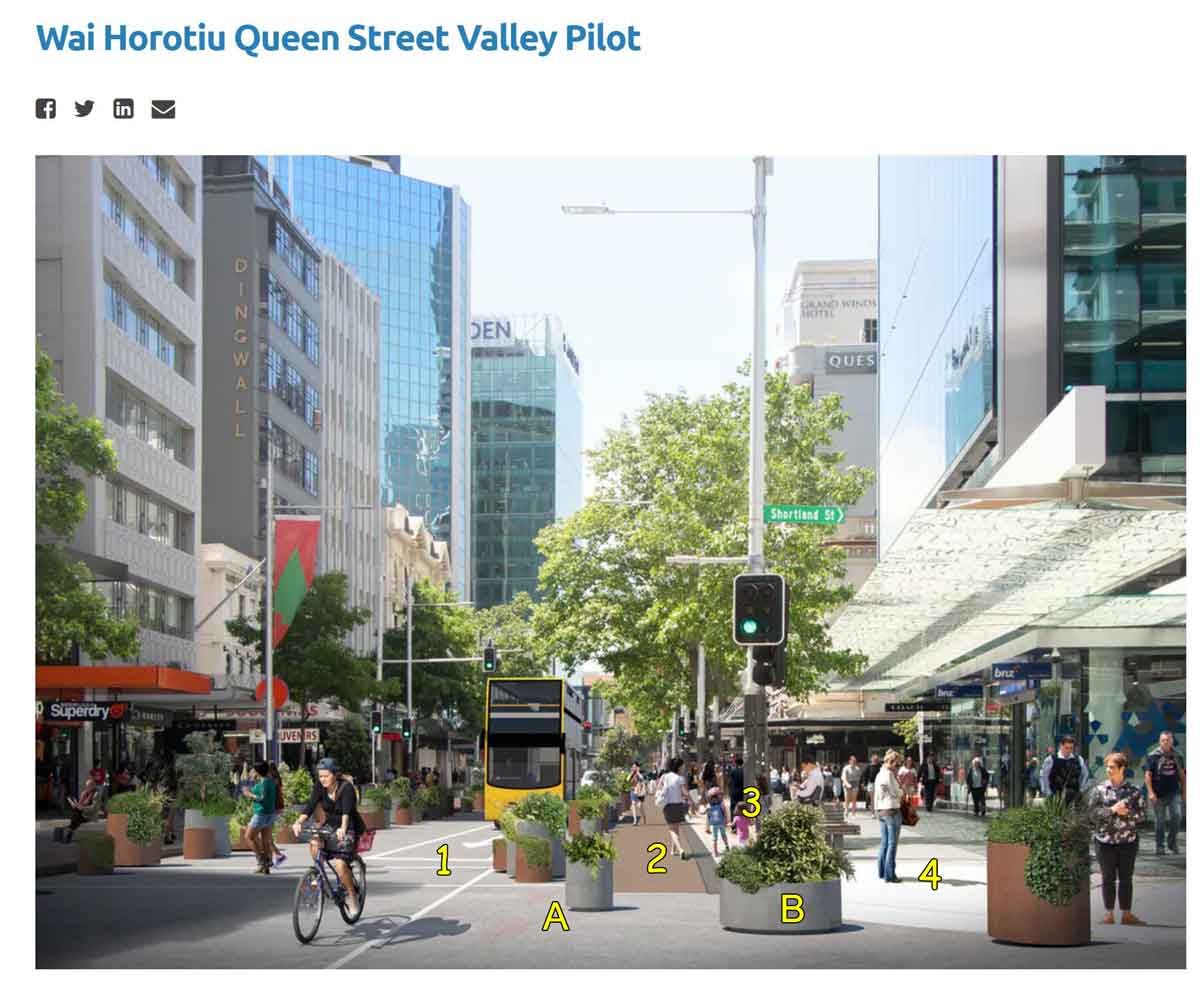

This is an artist rendition of the proposed redesign of lower Queen Street in Auckland – the principle commercial street in the centre of the largest city in NZ.

From the perspective of a cyclist, it is dangerous. But of greater concern is the culture of the Auckland Council that created it.

The problems with the design

The lane marked 1 is a shared lane for cyclists and buses. As the rendition shows, the bus fills the width of the street. And as the plan sets out, those buses are intended to make this part of Queen St their destination. That means they will stop in the street to allow passengers to get off and on. The cyclist who is not using Queen St as a destination, but a thoroughfare – trying to get from point A (such as Upper Queen St) to point B (such as the ferry terminal or train station) has to stop and wait.

In real life, the cyclist will try to get around, and it will only be a matter of time before a cyclist is struck by an oncoming car, truck or bus, or that a pedestrian will dart from behind the bus to cross the road and be struck by the cyclist.

Queen Street is very wide – about 25 metres from side to side. About 5-6 metres of Queen St is allocated for two vehicle/cycle lanes. The area marked Area A is allocated for potted plants, taking up almost as much width as the vehicle lane. Then the area marked Area 2 is this odd use of space, ostensibly for more pedestrians, apparently waiting bus passengers, although in 2020 it was an ill-conceived COVID-19 zone supposedly to allow 2 metre separation on a street that during COVID became a dead zone.

The area marked Area 3 is dedicated to signs, seating and where adjacent buildings leave their trash bags for collection. And finally the area marked Area 4 is the proper pedestrian zone, set out by a previous generation of planners who understood urban street design.

This is the reality of what it looks like when they finished it. Not as pretty as the artist rendition, but just as dangerous.

The problem with the council culture

The editor of SlowCycles was invited to participate in the Wai Horotiu Queen Street Project and did so as a cycling advocate. On request, a one-to-one walk-about meeting was set up with the Council project leader. The leader heard the SlowCycles concerns and replied that the proposed design had been peer-reviewed by a team of 20 experts and deemed proper, thus the views of SlowCycles were of no effect. Why hold public workshops for feedback if the real decision-making is by a group of 20 peers?

What was more telling, however, was the project manager’s answer to where he lived and how he commuted to work. Lives on the North Shore. Commutes by car over the Harbour Bridge to an underground Auckland Council carpark. In other words, a do-as-I-say-not-as-I-do bureaucrat. It would be interesting to know how many of the 20 peers will be riding cycles on lower Queen St as part of their transport regime. Unfortunately, due to privacy laws, that cannot be disclosed.

How it should have been designed

How it should have been designed

AVOID: Because cyclists are using Queen St as a thoroughfare, the first question should ask if there is a better route. Is it best practice to run the cycleway on Queen St? Would it be better to signpost a cycle thoroughfare using parallel streets such as Fort Lane, Jean Batten Place and High Street?

CENTRE LANES: If avoid is not workable, and Queen St must be used, make separate cycle lanes. Because they are used as a thoroughfare, the best design places cycle lanes in the middle (Area 1 in the drawing above) and the bus lane in Area A and 2, with passengers waiting in Area B. If instead the cycle lane is in Area 2, there is a risk of cyclists striking disembarking bus passengers. But even that is better than vehicles and cyclists sharing Area 1. And however it is done, be aware that crashing into big plant pots hurts.

What actually is happening

This photo shows is the final result. The reality is not so pretty as the artist rendition, but the narrow combined motor vehicle/cycle lane is in place. Imagine you are a cyclist trying to keep moving when the bus is stopped. Not a lot of room to get by. In the distance on the left, note the bus stop. The bus blocks the road.

And none of this came cheap. That redesign cost millions of dollars. The jumble of potted plants is not beautiful, it looks like a discount plant store.

Survival in a hostile environment

Cyclists are like rabbits living in elephant territory. They presume they are invisible and have zero protection. The smart ones do not run on elephant trails. The oblivious novices are culled. With the renovations to Queen St, savvy cyclists use the bus lane when there are no buses, then shift to the footpaths to keep moving, dodging pedestrians and e-scooters. They cross intersections on the pedestrian lights – sometimes walking, sometimes coasting and sometimes zigzagging to avoid pedestrians. They move to the footpaths, and use back streets like Elliot St and the footpath by the Council offices. However, all of this is stressful and streetwise, not part of a well-designed cycle plan to get around the city. From time to time, it involves surprises, near misses, discomfort for pedestrians – all because of plans developed by desk workers who don’t cycle their city.

The Bigger Picture

SlowCycles attended the workshop to advocate for cyclists. But in the room were other, very angry stakeholders. Building owners need courier delivery vehicles and tradies to have access – try carrying heavy tools and supplies from the nearest $40/day carpark building. Shops need customer access, sometimes as simple as a two-minute carpark to drop off shoppers or collect packages. Taxi and Uber drivers need places to drop and collect passengers. Residents of the CBD (that is the size of a medium NZ city) found the continual construction to be maddening. There were a lot of constituencies represented who were there because they were furious. Their needs were not being met. Their concerns however were not addressed. The workshops were about presenting decisions already made.

The workshops were not privy to the backroom discussions where real decisions were made. The people running the workshops appeared to work for the council, but on asking, turned out to be nice but powerless consultants. The workshops where feedback was billed found the airtime occupied by consultants making what amounted to sales pitches, burning up precious workshop time until the annoyed participants began to interrupt to ask pointed questions – for which there were no substantive answers or indications the decision-makers were going to change their plans based on vocal constituent need.

Now, two years on, the fact is the CBD is now a hollow shell littered with failed businesses – not big global franchises and chains that can survive it, but the entrepreneurs with a dream that gave the CBD its character. People lost their life investments. Some pivoted out of the CBD, others quit, salvaging the wreckage of their lives and dreams. A few made business decisions that the CBD no longer was profitable, so they relocated, leaving landlords with For Rent signs. None of this collateral damage is reported in the press. The only testimony are the vacant storefronts.

Part of the cause is no planning when tearing up streets. Instead of coordinating all the public and private sector needs to close streets, erect barriers and disrupt business life, and requiring a use-it-or-lose-it window when all must do their work at the same time, a site will be torn up, finally completed, then another party, public or private comes in and repeats the process. Temporary road and building works becomes a permanent state of disruption.

COVID was a major disruption, but even it became an Auckland Council / AT debacle.

The council and its CCO took advantage of the crisis to spend almost $1 million installing plastic bollards ostensibly to provide 2 m separation, but more likely to use the crisis to begin to drive private motor vehicles from lower Queen St. The result was not only ugly and useless, it was catastrophic for businesses who lost their customer base. Someone should be held accountable, but the institutions are so insulated, accountability is impossible.

And when they do put in cycle lanes, they are embarrassingly bad. The execution of cycle lane plans is being done by inadequately trained personnel.

But these are symptoms. The cause is the lacks of checks and balances – the shielding of council urban planners, both in council and Auckland Transport, from the affected people and businesses. Instead, the council and its CCO’s have created protected bubbles where they talk with their peers. As they lose contact with views counter to their own, their plans take on a life of their own. Those who try to break through the barriers are branded as contrarians as a tribal culture of us-vs-them takes hold.

This is a political problem. It needs to be fixed by the elected officials who must stop letting the bureaucracy define the terms of elected office. Checks and balances must be put in place, and the institutional bubbles broken.