Best Practice – Can NZ Learn from the EU?

A 50-year Head Start

In 1973, OPEC began an oil embargo, shocking Europe. Like most of the first world, it had turned to cars as a primary form of transport, shoving bicycles into the margins. Thus, half a century ago, it began to build a modern infrastructure for cycling – or at least in the regions that were relatively flat. It now has a network of over 90,000 km of dedicated cycle routes. And in the process, it developed best practice.

About 40 years later, New Zealand began to develop a cycling infrastructure. The reason it took longer is because much of the urban landscape is hilly, and it took the introduction of ebikes to flatten the hills and create a broader base of cyclists than the lycra-clad aficionados that lacked a critical mass. That and attention to climate change.

As a newcomer to cycling infrastructure, transport planners are well advised to educate themselves on what took half a century to refine before making it up as they go.

And to start, consider this basic principle in EU cycle route selection:

Avoid arterials unless there is no other way to create the cycle route.

“Why reinvent the wheel? Before writing rules and building roads for cyclists, visit the EU. Read their web sites. Learn what works.”

EU Characteristics of Cycle Roads

- Continuous, long distance paved routes that facilitate reasonable cycling speeds

- Independent of existing carriageways and motorised traffic

- Offer strategic, functional routes that connect residential, commercial and business areas.

- Integrated into the existing cycling network and other transport modes

- Bi-directional and have a greater width than a cycle track

- Often begin in rural areas but can continue into urban areas through green spaces & cycle streets, motor vehicles traffic excluded.

- Often have a name, logo, signposting and other branding.

- For all types of bicycles to easily use the highway, including cargo bikes and ebikes

EuroVelo Guidance on THE route development process

Principles for route selection and development (these should be considered

in conjunction with the needs of specific user groups):

- Safety – avoid public roads with large motor traffic volumes and high speeds.

Provide safe junctions. Consider social safety - Attractiveness – include and connect cultural, historical and natural sights,

culinary or other attractions, whilst avoiding unpleasant areas - Coherence and directness – provide uninterrupted route infrastructure but link to

attractions connected to the theme of the route and provide signing.

Avoid unnecessary detours - Comfort – minimise elevation. Provide good surfaces and sufficient good quality

services (accommodation, food, bike repair etc).

EU Guidance for city networks

Cycle networks have been defined as “an interconnected set of safe and direct cycling routes covering a given area or city”

EU Guidance for Rural Networks

A cycle highway is a high-quality functional cycling route that focuses on encouraging long-distance cycling. It can be made up of cycle lanes, cycle tracks or routes separate from the existing road infrastructure.

Memo to Auckland Transport and Auckland Council CCO Oversight committee

The worst place to place a cycle route is along an arterial or principle road. The best place is through a park, or on a dedicated cycle road. Intermediate solution is on back roads with few cars and no buses.

Why does Auckland Transport (AT) insist on removing on-street shopper parking, cutting down road lanes and installing cycle paths where cyclists breathe truck and bus fumes; finding themselves pitted against shop keepers, drivers and other road users? Cycle lanes along arterial and principle roads are hazardous at vehicle crossings because the cyclist is invisible to the driver.

The answer probably is inexperience. The planners are not cyclists who use the infrastructure. Instead, they go to books and studies, written by people with credentials, but not real-world experience. This web site dedicates itself to a different approach – search out patterns that work and assemble them in a sequence that can guide effective planning.

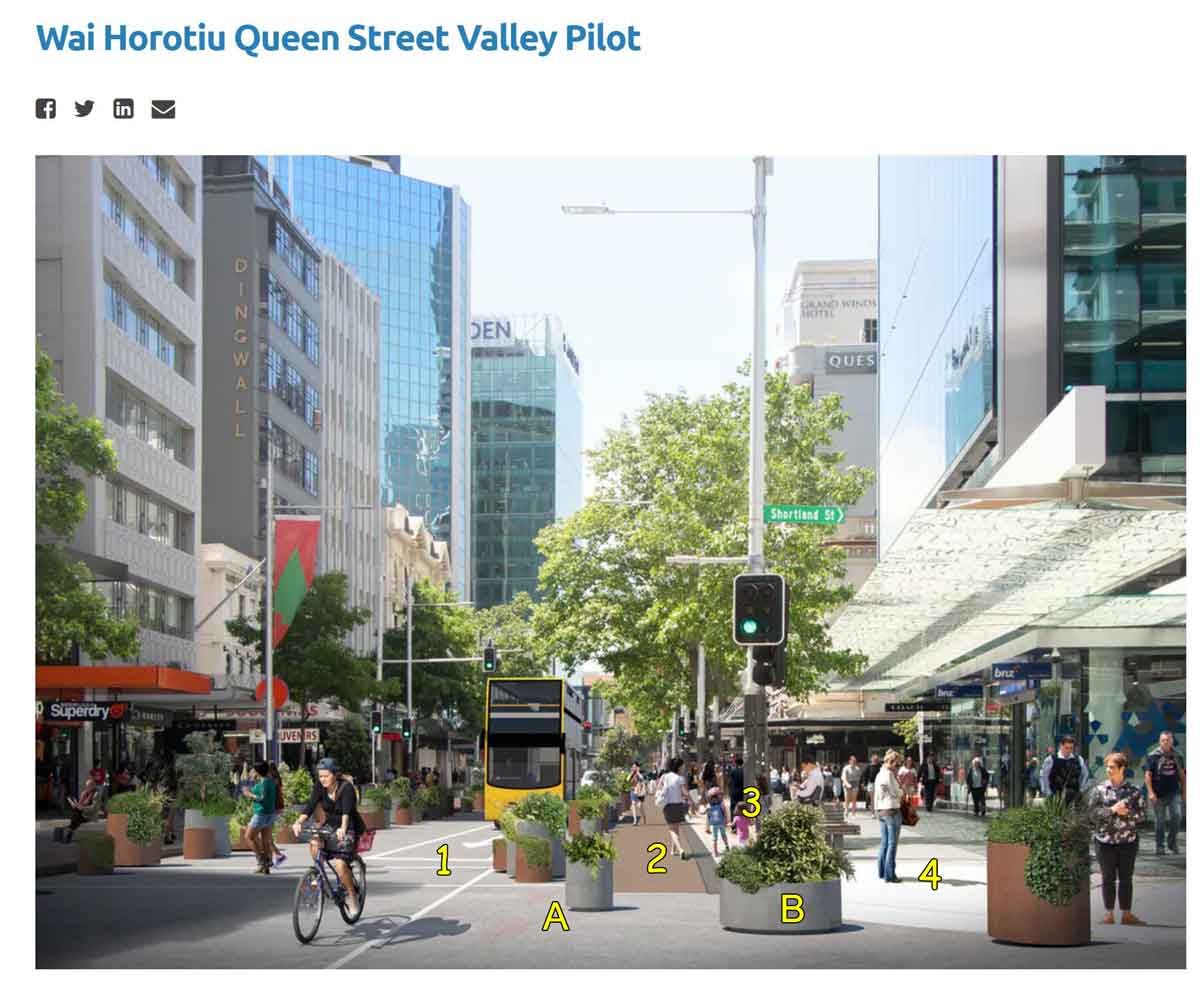

What’s wrong with this picture?

Lane 1 is a shared bus and cycle lane. The cyclist is using it as a through street, the buses as a destination. It is too narrow, the bus fills it. It will only be a matter of time before a cyclist is struck trying to get past a stopped bus.

Meanwhile Lane A and B take valuable street width for plants. Pedestrians get Lanes 2, 3 & 4.